Horry County S.C. Representative William Bailey has put tremendous time, effort, and resources into a plan for helping Horry County flood victims.

Residents living along the Waccamaw River in Conway and Longs, S.C. have experienced record flooding over the past 3 years.

What were supposed to be 100 year floods have now become common in Horry County.

In Socastee, S.C., residents have organized in an effort to demand S.C. state government take action.

A September study produced by Clemson University offers both clarity and hope for these families.

Said District 104 Representative William Bailey, “Educators from Clemson have contributed by helping us define the scope of what a greenway would look like. This concept would be so much more than a spillway for storm relief. “

THE REPORT READS

Evaluating Options and Alternatives for a Diversion Canal to Mitigate Waccamaw River

Floodwaters in the Conway, SC Area

Prepared for: Michael Wright, Clemson Legislative Affairs

Prepared by: Daniel R. Hitchcock, Ph.D., P.E., Chuck Jarman, P.E., Amy Scaroni, Ph.D., Skip Van Bloem, Ph.D., Tom Williams, Ph.D. (Clemson – Baruch Institute, Georgetown, SC) and Anand

Jayakaran, Ph.D., P.E. (Washington State University)

Date: September 1, 2020

Background

As per the USACE report “Concept Study of a Flood Reduction Diversion Canal” prepared for Horry County (April 2009), a flood diversion canal has been proposed to transfer Waccamaw River water from upstream and northeast of Conway to the Atlantic Intercoastal Waterway (AIWW) near Little River, SC. A long history is available in the USACE report.

Our team learned more about recent concepts for the proposed canal not included in the report, such as the inclusion of open space and a recreational greenway that would intentionally flood during large flow events, while providing access during normal flow conditions. The potential for mitigation due to possible impacts to local jurisdictional wetlands from the diversion canal was also discussed, as well as expanding flow access to existing wetlands to support flood management.

Canal Design Recommendations

If the construction of the canal were to go forward, we have two primary recommendations for the actual proposed canal design: (1) create sinuosity, and (2) incorporate a two-stage bank design.

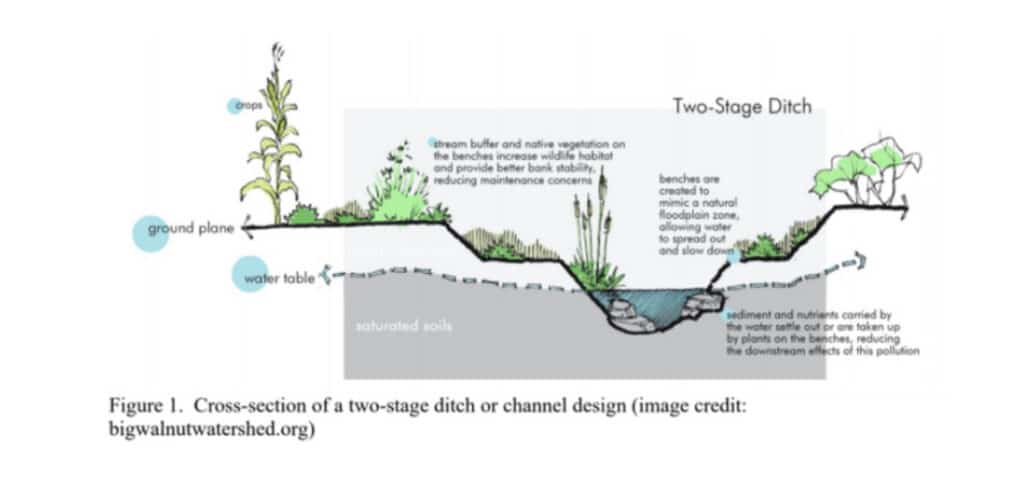

(Figure 1). Creating a sinuous or a meandering flow path, although requiring more land area, would allow for the dissipation of energy in the river system, especially during high flows, resulting in a reduction of stream bank erosion. The two-stage channel design – ideal for a greenway or other potential recreational uses – provides a lower smaller channel to carry normal flows and a wider “floodplain” to accommodate and slow larger flows.

The wider flow area (termed benches in Fig 1) should be planted to create a more natural floodplain. This area could also be used for temporary recreational trails and to provide boating and fishing access.

These planted areas also provide natural habitat benefits, help remove sediment and associated pollutants, and stabilize riverbanks.

Alternatives or Complementary Options

The team discussed four primary alternatives to complement and/or replace the canal diversion.

Option: (1) a watershed-based plan

Option: (2) incorporating green infrastructure and runoff reduction strategies upstream of and within flood-prone areas

Option (3) wetland protection/utilization/restoration

Option (4) education and outreach programs for residents, business owners, and decision-makers.

A watershed-based plan can be used to evaluate land use, land cover, soil types and respective drainage characteristics within the delineated basin, to help determine strategies for reducing runoff and protecting water quality, habitat, and human life and property. An example of a watershed plan can be found at https://www.wrcog.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Murrells-Inlet-Watershed-Plan-Part A.pdf

– a SCDHEC-funded effort led by the Waccamaw Regional Council of Governments, that – with deliberate and iterative stakeholder involvement and community engagement – was developed and implemented to attempt to reduce runoff and bacteria contamination to shellfish harvesting beds.

One potential solution related to watershed planning would be the use of green infrastructure – designed systems that mimic natural hydrology and ecology (e.g. constructed wetlands, rain gardens, bioretention cells) – that can be utilized for runoff reduction and water quality improvement. The use of permeable paving materials would also aid in runoff reduction and flood management in throughout the watershed. For further runoff reduction, local rainwater harvesting (rain barrels and cisterns) can be employed to collect runoff water and deter it from flowing off properties and entering waterways. These smaller scale options would require routine inspection and maintenance to support effective performance. On a much larger scale, natural wetland areas could be strategically incorporated into the plan to assist in flood mitigation across the watershed, also protecting water quality and habitat. Currently, these floodplain areas and “swamps” provide water storage during large events, but as we know, this is not nearly enough to mitigate all flooding from our more recent and unprecedented larger storms and river flows. Clemson Extension has several existing education and outreach programs to assist with these endeavors, and new programs that target location-specific users in the watershed and along the river could be developed. A variety of program examples can be found at https://www.clemson.edu/extension/water/index.html.

We could help further develop these options, depending on the desires of state and local resource managers and administrations.

Other Considerations and Resources

We do recognize the “new normal” reality of stronger storms with more intense and longer duration rain events, higher river stages and flows, and the vulnerability of – and potential risk to – property and life. We also know that the area of concern has a low gradient topography (flat), has shallow water table conditions dominated by wetland areas, and is relatively densely populated along certain reaches of the Waccamaw River, all posing unique water-management challenges to our region. The Waccamaw River is a complex system that includes tidal influence and potential backwater flooding, as well as backwater influence from the Great Pee Dee River’s connections downstream. A combination of the above approaches could allow for flood mitigation, whether at the local scale, the watershed/basin scale, or both. To further support these considerations, The Nature Conservancy has conducted economic analyses of impacts from Hurricane Florence for northeastern SC (Georgetown and Horry Counties, summary and full report attached). Also, our Clemson-Baruch Institute team, based in Georgetown, SC – with efforts led primarily by Dr. Tom Williams, Emeritus Professor – has worked over the past several years to evaluate river stage and flow data in these waterways. More specifically, the connectivity between the Waccamaw and Great Pee Dee Rivers, coupled with downstream tidal influence, have been of great interest, with a major focus on the recent flood events from Hurricanes Matthew and Florence, as well as TS Bertha. This latter work is in review for publication in the Journal of South Carolina Water Resources along with another relevant publication Williams et al., 2019 (https://doi.org/10.34068/JSCWR.06.04).