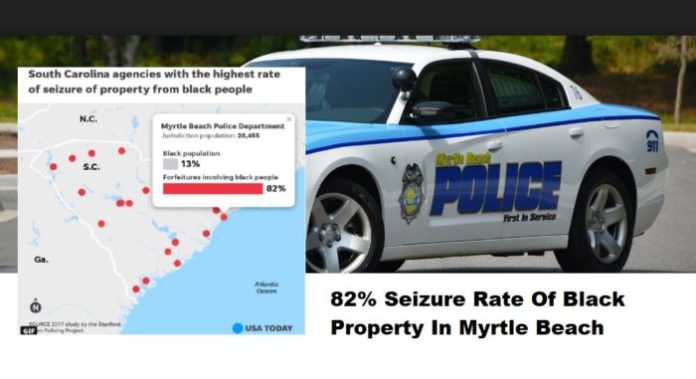

USA TODAY – Greenvilleonline.com Investigative Report Shows 82% Seizure Rates On Blacks In Myrtle Beach Area

This article was written entirely by GreenvilleOnline.com as part of its Taken Series.

Greenville attorney Jake Erwin said the overarching idea is that the money being seized is earnings from past drug sales, so it’s fair game. “In theory, that makes a little bit of sense,” he said. “The problem is that they don’t really have to prove that.”

When Brandy Cooke dropped her friend off at a Myrtle Beach sports bar as a favor, drug enforcement agents swarmed her in the parking lot and found $4,670 in the car.

Her friend was wanted in a drug distribution case, but Cooke wasn’t involved. She had no drugs and was never charged in the 2014 bust. Agents seized her money anyway.

She worked as a waitress and carried cash because she didn’t have a checking account. She spent more than a year trying to get her money back.

[SC] Police are systematically seizing cash and property — many times from people who aren’t guilty of a crime — netting millions of dollars each year. South Carolina law enforcement profits from this policing tactic: the bulk of the money ends up in its possession.

The intent is to give law enforcement a tool to use against nefarious organizations by grabbing the fruits of their illegal deeds and using the proceeds to fight more crime.

“It’s a dirty little secret. It’s so consistent with the issue of how law enforcement functions. They say, ‘Oh yeah, we want to make sure that resources used for the trafficking of drugs are stopped’ … but many of the people they are taking money from are not drug traffickers or even users.”

These seizures leave thousands of citizens without their cash and belongings or reliable means to get them back. They target black men most, our investigation found — with crushing consequences when life savings or a small business payroll is taken.

Many people never get their money back. Or they have to fight to have their property returned and incur high attorney fees.

Police officials respond by saying forfeiture allows them to hamstring crime rings and take money from drug dealers, a move they say hurts trafficking more than taking their drugs.

In 2016, when a Myrtle Beach police unit broke up a sophisticated drug ring called the 24/7 Boyz that offered a dispatch system to order drugs and have them delivered on demand, the police used seizure powers. They took cars, firearms, a four-bedroom house and $80,000. They also arrested 12 people.

Fifteenth Circuit Solicitor Jimmy Richardson initially prosecuted the case before turning it over to the federal government. In January, 10 of the 12 defendants pleaded guilty to drug conspiracy charges.

Richardson said taking a drug ring’s operating cash strikes a critical blow against traffickers in a way that criminal charges don’t. “A drug enterprise is an onion, it’s a multitude of layers,” he said. “Some tools hurt the traffickers, some hurt the enterprise itself. I feel this hurts the enterprise.”

Black men pay the price for this program. They represent 13 percent of the state’s population. Yet 65 percent of all citizens targeted for civil forfeiture in the state are black males.

“These types of civil asset forfeiture practices are going to put a heavier burden on lower-income people,” said Ngozi Ndulue, recently a national NAACP senior director, now working at the Death Penalty Information Center. “And when you add in racial disparities around policing and traffic stops and arrest and prosecution, we know this is going to have a disproportionate effect on black communities.”

In The State Of SC

• If you are white, you are twice as likely to get your money back than if you are black.

• Nearly one-fifth of people who had their assets seized weren’t charged with a related crime. Out of more than 4,000 people hit with civil forfeiture over three years, 19 percent were never arrested. They may have left a police encounter without so much as a traffic ticket. But they also left without their cash.

Roughly the same number — nearly 800 people — were charged with a crime but not convicted.

Greenville attorney Jake Erwin said the overarching idea is that the money being seized is earnings from past drug sales, so it’s fair game. “In theory, that makes a little bit of sense,” he said. “The problem is that they don’t really have to prove that.”

In some states, the suspicions behind a civil forfeiture must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt in court, but there is no requirement of proof in South Carolina. When a forfeiture is contested, prosecutors only have to show a preponderance of evidence to keep seized goods.

Police don’t just seize cash.

Practically anything can be confiscated and sold at auction: jewelry, electronics, firearms, boats, RVs. In South Carolina, 95 percent of forfeiture revenue goes back to law enforcement. The rest is deposited into the state’s general fund.

Most of the money isn’t coming from kingpins or money laundering operations. It’s coming from hundreds of encounters where police take smaller amounts of cash, often when they find regular people with drugs for personal use. Customers, not dealers. More than 55 percent of the time when police seized cash, they took less than $1,000.

• Your cash or property can disappear in minutes but take years to get back. The average time between when property is seized and when a prosecutor files for forfeiture is 304 days, with the items in custody the whole time. Often, it’s far longer, well beyond the two-year period state law allows for a civil case to be filed. But only rarely are prosecutors called out for missing the filing window and forced to return property to owners.

• The entire burden of recovering property is on the citizens, who must prove the goods belong to them and were obtained legally. Since it’s not a criminal case, an attorney isn’t provided. Citizens are left to figure out a complex court process on their own. Once cases are filed, they have 30 days to respond. Most of the time, they give up.

The bulk of forfeited money finances law enforcement, but there’s little oversight of what is seized or how it’s spent. Police use it to pay for new guns and gear, for training and meals and for food for their police dogs. In one case, the Spartanburg County sheriff kept a top-of-the-line pick-up truck as his official vehicle and sold countless other items at auctions.

In many other places, changes are being made: 29 states have taken steps to reform their forfeiture process. Fifteen states now require a criminal conviction before property can be forfeited, according to the Institute for Justice, a non-profit libertarian law firm.

South Carolina lawmakers have crafted reform bills in recent General Assembly sessions, but none of the efforts made it out of committee.

To critics, South Carolina is the poster child for the injustice inherent in the for-profit civil forfeiture system, said Louis Rulli, a law expert at the University of Pennsylvania.

Forfeiture doesn’t square with the rest of the justice system, Rulli said. “How could it be possible that my property could be taken when I am not even charged with any criminal offense? It seems un-American,” he said.

Those who pay the biggest price are black men. Men like Kinloch. While he was hospitalized for a head injury from a home intruder, North Charleston police removed money from the tattoo artist’s apartment.

That department earns 12 percent of their annual operating budget from cash and property seized under civil law, our investigation shows.

“The robber didn’t get anything, but the police got everything,” said the 28-year-old Kinloch.

Police charged him with possession with intent to distribute after finding the marijuana in his apartment, but the charge was dismissed.

Kinloch never got his cash back.

Rent was due.

Without his $1,800, he couldn’t pay the landlord and was forced out of his home.

CONWAY, HORRY COUNTY, AND SC PROBLEM AS WELL

Ella Bromell, a 72-year-old widow from Conway, twice nearly lost her home, though she’s never been convicted of a crime in her life.

Yet the city of Conway nearly succeeded in seizing her house because they said she didn’t do enough to stop crime happening on the sidewalk and in her yard. Young men were using her lawn as a location to sell drugs at night, according to court records.

The fight between Conway officials and Bromell, who is black, began in 2007 and lasted a decade — culminating in court in 2017 when two judges sided with her and wrote that the city “failed to produce any evidence that the residence was an integral or otherwise fundamental part of illegal drug activity.”

Still, Bromell fears the city will try again, despite the police admission in court that they couldn’t say if she was even aware of a single drug sale around her house.

Conway City Manager Adam Emrick said the city has contemplated future seizures in the case of Bromell or similar property owners.

Losing her home would be the end of her, Bromell said. “I don’t want to go nowhere else.”

More: She gave her friend a ride and lost her wages

Thurmond Brooker, Bromell’s attorney, said the law is being warped without the public even noticing. “It’s being used in a way in which innocent people can have their property taken,” he said. “Little old ladies whose property is being trespassed upon can be victimized for a second time.”

Why are black citizens like Bromell facing forfeiture more often than their white neighbors?

One police official said it’s because there’s more drug crime in the black community.